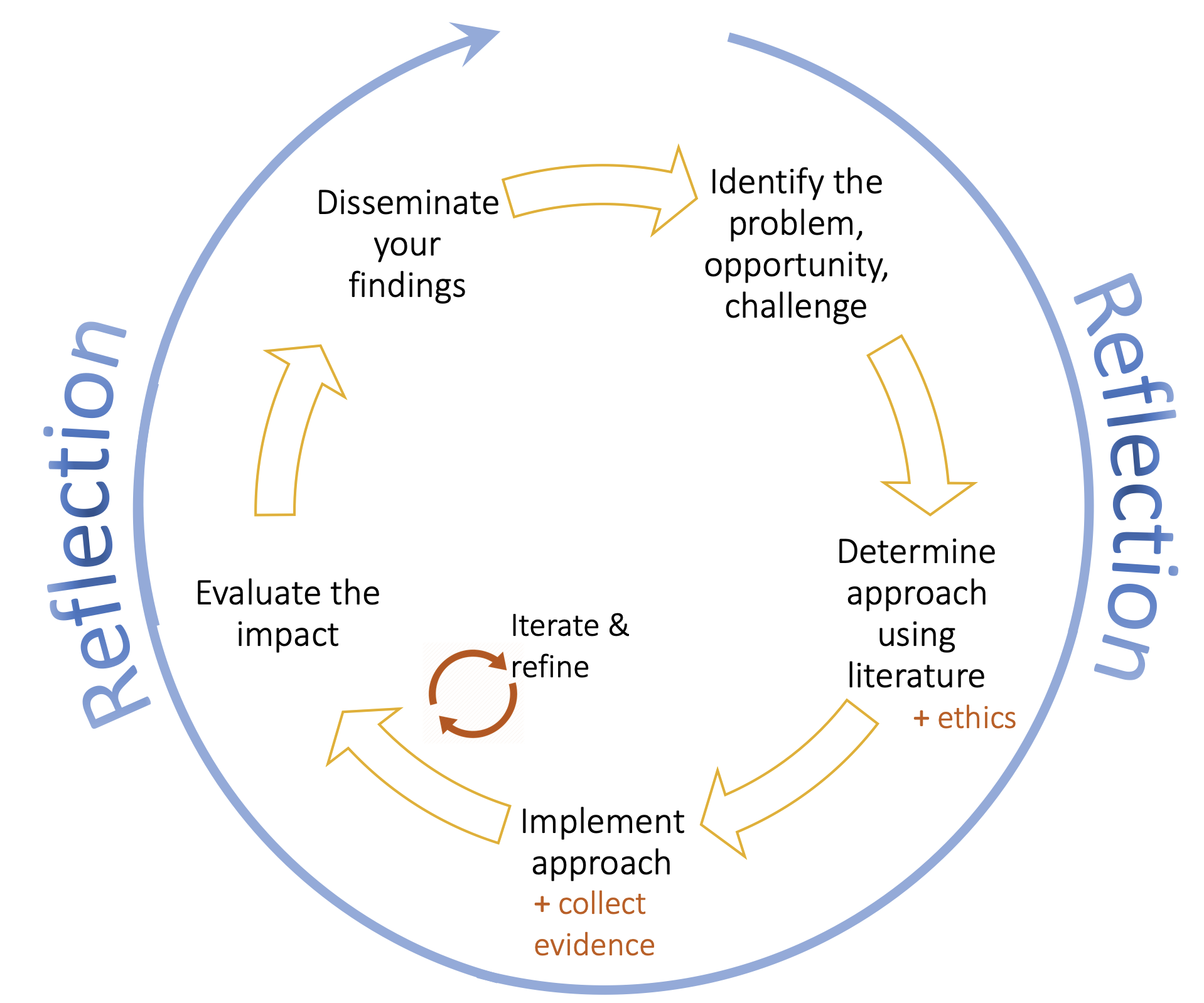

In the previous post, we looked at how research and SoTL were similar yet different. As part of that, the SoTL cycle was presented in a way that shows the SoTL process, even though it is not always as linear and neat as the graphic depicted (shown below for reference). However, within this cycle, there is one component that is always present: reflection. Reflection is an important part of being a SoTL scholar as SoTL is focused on our own practice and ways to improve it.

Figure 1. SoTL cycle depiction (but note that it is not always as linear and organised as appears!).

What is reflection in SoTL?

Firstly, let's begin by defining reflection in general, and then we'll look at what it means for our SoTL practice. Reflection can be simply defined as the process of considering something deeply that we might not have thought much about otherwise. In education, we often refer to critical reflection and critically reflective practice and practitioners. Dewey (1910, p. 6) wrote that reflective thought involves the "active, persistent, and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it". This indicates that reflection - reflective thought and subsequently reflective practice - requires a questioning mindset by considering why things are the way they are and how they might be in the future. Taking this further, Brookfield (2017, p. 3) defined critical reflection as "the sustained and intentional process of identifying and checking the accuracy and validity of our teaching assumptions". Bringing this back to our SoTL process, reflection is the continual process of interrogating our assumptions about our SoTL problem, the evidence that we are seeing in our practice that supports or contradicts our assumptions, and considering the possibilities for future practice.

What models of reflection can be used to support our critically reflective practice?

Perhaps one of the most effective ways to understand reflection and critically reflective practice is to look at some models that can be used to support this and examples of these models in practice. Each of the models presented below is an example of a method that can be used to support critical reflection, and there is no single "correct" way to reflect. You might find that it is a combination of these models that supports your reflection best. As we go through the models, they'll become progressively more complex.

Model 1: What? So what? Now what?

This is perhaps the simplest model and it gets to the heart of critical reflection quickly. It was developed by Rolfe et al. (2001) to support nurses to reflect in their practice. In essence, it is the following:

What? What happened? Describe the event in objective detail. Note that the event can be positive or negative - it just needs to be one that is in your mind for further consideration.

So what? What does this mean to you? Why was this event important to reflect on? Describe the importance of the event and why this event has stayed with you.

Now what? What will happen now or in the future? What is the connection to your future practice? This can include connections to the literature or ideas about looking into the literature on related topics or events.

For example, if you have had a negative online teaching experience, you may critically reflect on that. Here is a real-life example that I have experienced and subsequently reflected on.

What? A student in my postgraduate course had not engaged with the content required in order to fully develop their second assignment and only engaged with the feedback from their first assignment three days prior the second assignment being due. This resulted in a panicked message from them late at night, which I responded to the next day. The next engagement from the student was the submission of their second assignment, but the submission was incomplete and there were significant elements of self-plagiarism (even though this had been part of the extensive feedback on the first assignment).

So what? This is an indicator that my feedback is not being read in a timely manner. Perhaps it is the student's fault for not engaging, but this time it has meant that they (significantly) failed the second assignment, and subsequently the course. This is a problem for the student and also for me because I have an unhappy student who believes that they should have passed. Perhaps I need to review the scaffolding for the second assignment to see if it needs to be stronger, and I could place more emphasis on engaging with the feedback on the first assignment. How can I better support students like this? But if it was only one student in the course, how much is my responsibility and how much is theirs?

Now what? I will review my processes for feedback and how I can track which students have engaged with the feedback. Perhaps I should be sending nudges to those who have not engaged with the feedback at one week post-assignment return. An explicit discussion on academic integrity (including self-plagiarism) might also need to be incorporated into the course so that this type of incident does not arise again. I will also review the second assignment scaffolding and ask a colleague to review it. I will also look more into the literature on assessment design and scaffolding the skills needed to successfully complete the assessment item.

Watch the following video for a very brief (2:44 min) overview of this model.

Model 2: Brookfield's four lenses for reflection

Brookfield is a great proponent of critically reflective practice and critical thinking. “The critically reflective process happens when teachers discover and examine their assumptions by viewing their practice through four distinct, though interconnecting lenses’ (Brookfield, 2005, p xiii). He developed a model of reflective practice that focused on viewing events through four lenses:

our own autobiography as teachers and learners,

our students' eyes,

our colleagues’ experiences, and

the critical literature.

Each of these lenses provides a different perspective on the event, and this way we can better understand what happened and how we can move forward with it. The lenses are briefly described here, with links to individual videos for each lens from a higher education perspective.

Autobiographical lens (1:58): This is often referred to the as the "Self lens" and it focuses on our experiences as a teacher in order to reveal aspects of our pedagogy that may need adjustment or strengthening. Teaching philosophies and portfolios can be examples of this lens.

Learner's lens (2:13): This is our students' eyes - their perspectives. Engaging with their view of the learning environment can lead to more responsive teaching. Evaluations (formal and informal), assessments, journals, focus groups, and/or interviews can each provide cues to improve teaching and learning.

Peer lens (1:40): This is our colleagues' experiences and perceptions - both our informal and formal conversations that we engage with and seek out when trying to understand an event. Our colleagues can help highlight hidden habits in our teaching practice and also provide different approaches to teaching problems. Also, colleagues can be inspirational and provide support and solidarity. Peer observation is an example of this lens.

Theoretical lens (1:34): This refers to what the literature says about our problem or opportunity. That is, we seek perspectives and experiences from the literature to inform our understandings. Teaching theory provides the vocabulary for teaching practice and offers different ways to view and understand our teaching.

These lenses can be helpful in better understanding our context and problem/opportunity, and this can be a multi-faceted approach to more critically reflecting on our teaching and learning.

Model 3: 4Rs of reflection

The 4Rs model of reflection presented by Bain et al. (2002) focuses on four actions that we can take as part of our critically reflective practice in teaching and learning. These actions are report/respond, relate, reason, and reconstruct. Note that some refer to this as the 5Rs model because they separate the first R into two actions (report and then respond).

Report/Respond: A descriptive account of the situation, incident, or issue, and an emotional or personal response to the situation, incident, or issue

Relate: Drawing a relationship between current personal or theoretical understandings and the situation, incident or issue

Reason: An exploration, interrogation or explanation of the situation, incident or issue

Reconstruct: Drawing a conclusion and developing a future action plan based upon a reasoned understanding of the situation, incident or issue

A brief overview of these 4Rs is in the infographic below.

Source: 4Rs model of reflection

If you'd like to view a video to explain this further, then watch this short explanation (3:35) by Associate Professor Rachael Hains-Wesson. An example of this model in practice can be found here and also here.

Other commonly used models

Of course, there are other models of reflection, and they are most effective when you find the one that suits you and your way of thinking. While you can search for models online, here are some that are commonly used in higher education:

Questions for you

Have you seen or heard of these models before? If so, have you used any of them?

Which model speaks to you most?

Which model do you think you will use in your project? Will all of your team members use the same model?

Connection to your L&T project

Let's connect this back to your L&T project. As you have seen through this post and the SoTL content on what it is and how it differs to research, reflection is an important part of the SoTL cycle. Even to be in the position that you are in now in your project indicates that you have reflected on a challenge or opportunity that you face in your teaching. Here are some questions that you can consider among your team.

How will your team reflect on the L&T project?

Will you focus on individual reflections or team reflections?

As reflections are part of the reporting process, do you have a plan about how to manage this in terms what the focus of the reflection will be and how you will present a cohesive reflection?

Further reading

The further reading for reflection is SoTL is embedded in the content on the models of reflection above, but these two can be added as general resources for investigating more into reflection.

Ainsworth, S. (2005). Becoming a relational academic. Synergy. 22.

Dobbins, K. (2011). Personal reflection: Reflections on SoTL by a casual lecturer: personal benefits, long-term challenges. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 5(2), art. 24. doi:10.20429/ijsotl.2011.050224

Teaching and Assessing Reflection in Higher Education (USQ staff access only)

References

Bain, J.D., Ballantyne, R., Mills, C., & Lester, N.C. (2002). Reflecting on practice: Student Teachers' perspectives. Flaxton, Qld, Australia: Post Pressed.

Brookfield, S.D. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA.

Dewey, J. (1910) How we think. D.C. Health & Co.: Boston, MA.

Rolfe, G., Freshwater, D., Jasper, M. (2001) Critical reflection in nursing and the helping professions: a user’s guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.